The Real Threat No One's Talking About

While the media obsesses over sophisticated deep fake voice cloning, because it creates outrage and drives clicks, the real threat to contact centres are the cheap fakes (generic synthetic speech) that are already attacking your call centre and will increase exponentially in the next few years.

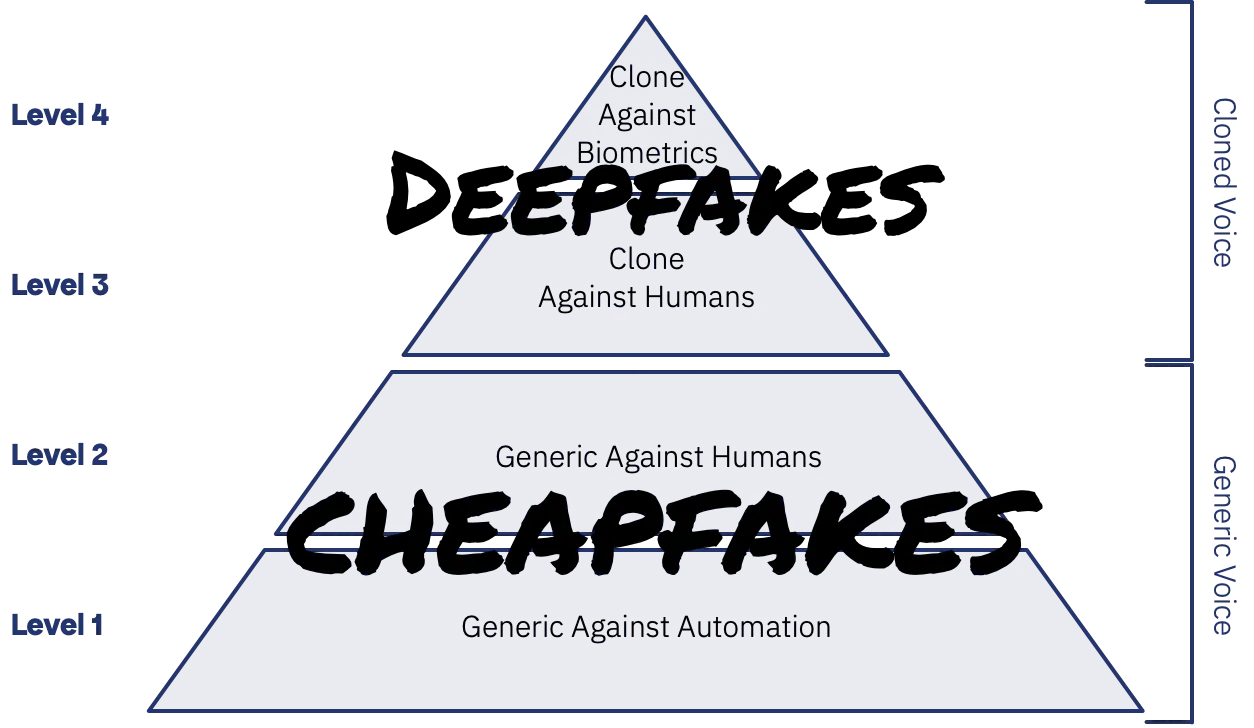

I previously laid out a hierarchy of synthetic speech threats that organisations should use to identify and categorise the risk this technology presents to your organisation. I now want to focus on the very real threat from cheapfakes, these attacks at Level 1 (against automation) and Level 2 (against human agents) are the key risks that most call centres face today.

These attacks use commodity synthetic speech from major cloud providers and self-hosted solutions to achieve anonymity and a scale of attack that wouldn’t have been possible when relying on humans to make the calls. They are used to attack automated systems and when combined with large language models can also be effective against human agents. In practice, very few organisations have the mechanisms in place to detect, let alone prevent the exploitation of this technology.

Understanding these attack patterns is crucial groundwork, because when we combine cheapfakes with large language models, the implications extend far beyond individual securitySecurity is one of three key measures of Call Centre Security process performance. It is usually expressed as the likelihood that the process allows someone who isn't who they claim to be to access the service (False Accept). incidents to fundamentally challenge how we think about authenticationAuthentication is the call centre security process step in which a user's identity is confirmed. We check they are who they claim to be. It requires the use of one or more authentication factors. itself. But first, we need to understand what we're actually dealing with.

Understanding Cheapfakes in Practice

Synthetic speech using traditional text to speech (TTS) engines used to be slow or expensive to generate and sounded like a robot. Today it’s insanely quick and close to free to generate using off the shelf voices from major providers. Including, Amazon, Google, Microsoft, a host of specialised players like ElevenLabs and Resemble AI or any number of open-source libraries.

You obviously get what you pay for, and the cheaper versions can still sound a bit robotic but it doesn’t matter if it’s only talking to another robot. Ironically, when I’m testing systems, I often find that synthetic speech is often more likely to be correctly understood than my own voice. As an example of how cheap these can be, I recently completed a thousand calls to test a client’s voice automation system and the total cost of synthetic speech was less than $2.

Historically, some attackers automated the use of Dual Tone Multi Frequency (DTMF) in traditional Interactive Voice Response (IVRs), but the shift to conversational Natural Language and Speech Directed systems forced them to use real humans or attack elsewhere. This significantly reduced the value of this attack method. More recently, as voice-based solutions have become more capable and increasingly accessible for enterprises, the incentive and opportunity for attackers has returned.

The same technologies that enterprises are using to increase the usabilityUsability is the primary performance dimension of the security process. Get it right and both security and efficiency flow, but usability is all wrapped up in human psychology. It’s a complicated subject deeply linked to behaviour, not just that of customers, but also of call-centre agents. and capability of these solutions allow attacks with a scale and level of anonymity that humans don’t provide. Ironically, the better we make these systems and the more work shifts from human agents to automation, the bigger the attack surface we create.

As the technology becomes even more efficient and realistic, it provides a level of familiarity and responsiveness that makes its use against human agents increasingly viable. No more suspicious-sounding voices from overseas call centres, no suspicious pauses as attackers check information and thousands of simultaneous calls.

Related Articles

Four Attack Patterns You Need to Know

Information Harvesting (No/Partial Credentials)

Attackers use synthetic voices to systematically probe your voice automation, working with whatever information they have: sometimes just a phone number or card number. They aim to enrich what they do know to exploit it themselves or resell so someone else can. Just confirming the information they have belongs to a customer of yours can be enough to allow a more targeted social engineering attack.

The challenge for many organisations is that to be effective, voice automation needs to be useful and reduce friction for real customers. Getting the balance between securitySecurity is one of three key measures of Call Centre Security process performance. It is usually expressed as the likelihood that the process allows someone who isn't who they claim to be to access the service (False Accept). and usabilityUsability is the primary performance dimension of the security process. Get it right and both security and efficiency flow, but usability is all wrapped up in human psychology. It’s a complicated subject deeply linked to behaviour, not just that of customers, but also of call-centre agents. in the design of these systems is really challenging (it’s where I spend a lot of my time), but at least, with robust testing, we can be sure these systems will obey their rules. The same cannot be said for human agents and especially for the Large Language Model driven solutions that some organisations are now using, which might helpfully volunteer information that an intentionally designed IVR would never reveal.

Operational Surveillance (Has Credentials)

This pattern is different to harvesting because the attackers already have valid credentials: perhaps from a data breach, social engineering (using information harvested above), or because they’ve been provided by mule account owners.

They use synthetic voices in your automated systems to monitor these products and accounts, without the footprints that might be left if they did the same thing in digital channels. They're typically watching for salary deposits, periods of inactivity when fraudulent transactions might go unnoticed for longer, or an inbound payment they’ve tricked someone into making so that they can transfer it out again quickly.

As a proportion of total volume these calls are likely to be tiny and they blend into your normal traffic patterns so identifying them from pattern analysis alone is challenging. To make matters worse, they look like just the types of calls we want to encourage: genuine customers who had all their needs met in automation and didn’t need to speak to a human agent.

Active Exploitation

This is where attackers use synthetic voices as part of a more complex attack to extract value from you or your customers, orchestrating interactions across several channels or calls. Attackers may have a customer on one line whilst they exploit synthetic voice in your automated systems to extract more information, trigger messaging to deepen the customer’s belief they are talking to you or authorise a transaction.

The synthetic voice combined with related technologies such as speech to text, provides a consistency and scale that human accomplices can’t match. In some cases attackers might use these technologies to augment themselves but in others let their tools run autonomously, making thousands of calls. The technology removes many of the human factors that might ordinarily raise suspicion, such as hesitation or background noise. The increased speed of synthetic speech generation and naturalness of Large Language Model (LLM) conversations makes it possible to fully automate the social engineering of your customers today. It won’t be long until they’ll be able to fool even your most experienced agents, opening a far wider attack surface area.

Related Services

Agentic Interaction

This emerging pattern involves genuine customers using an AI assistant to interact with your services. “Call my bank and check my balance” may soon become a routine request to our personal assistants. I’m still not sure whether to call this attack but it’s certainly going to create a headache for many organisations.

The phone channel is particularly susceptible to this type of automation, as it’s significantly easier for today’s LLMs to understand the simple voice conversation than a complex web page. Phone systems also rarely have the same bot protections we employ in digital channels, more of which we will come to in my next article.

Similar to early online account aggregation solutions, the risk here is twofold: that customers provide their credentials to a third party that’s a honey pot for attackers and that the volume of these calls overwhelm your automated systems, or consume expensive human agent time to resolve.

Of course this is an emerging area and there are a plethora of potential solutions but they will take time to implement and be driven by the largest enterprises with the most to lose. For everyone else and whilst we wait for the market to shake out, the phone channel will provide a pragmatic shortcut for third parties selling their Agentic AI vision with you as their product.

Subscribe for New Content

Conclusion

The media and technology industry’s fixation on deepfakes has created a dangerous blindspot. While everyone worries about sophisticated voice cloning, cheap fakes are already quietly probing call centres and consumers with commodity synthetic speech that costs almost nothing.

The increased capability and enthusiasm for voice automation and self-service has dramatically expanded the enterprise attack surface area. Whether attackers are enriching information from data breaches, monitoring mule accounts or orchestrating multichannel social engineering campaigns, generic synthetic speech is becoming essential to their toolkit.

But this is just the beginning. When we combine cheapfakes with large language models, we're looking at something far more fundamental: the complete automation of social engineering. The implications for knowledge-based authenticationAuthentication is the call centre security process step in which a user's identity is confirmed. We check they are who they claim to be. It requires the use of one or more authentication factors. are profound, and I'll be exploring this strategic shift in my next article.

Fortunately, effective defences exist, strategies and technologies that can protect your organisation whilst still maintaining the usabilityUsability is the primary performance dimension of the security process. Get it right and both security and efficiency flow, but usability is all wrapped up in human psychology. It’s a complicated subject deeply linked to behaviour, not just that of customers, but also of call-centre agents. and effectiveness of voice automation. Synthetic speech detectionSynthetic Speech Detection is a mechanism used to protect Voice Biometrics systems from presentation attacks using synthetic speech. It relies on detecting characteristics inherent in the text-to-speech (TTS) generation process., network authentication, and behavioural analytics can be layered onto current voice automation without disrupting customer experience. The key is understanding which combinations provide the best protection for your specific attack surface, and I’ll cover this in the last of this mini-series.